A while ago on a Facebook birth forum I saw the phrase “you won’t grow a baby too big for you to birth”. It was a familiar phrase as it was something I would hear regularly on the homebirth e-group I was a member of back in 2010 when I was pregnant with my first. Back then I accepted it as the truth, but having been involved in #MatExp for nearly a year I have learned that few things to do with birth are that simple. So I asked the question on the #MatExp Facebook group:

What followed was a fascinating discussion. Information was shared from lots of different quarters, and evidence was linked to. Experienced birth practitioners shared their views and a few themes started to appear. All along I knew I was intending to write up the discussion as a blog post so I was trying to keep up with the information and understand what was being said. As I opened up links to studies, trials, journal articles and so on my heart sank as I am not the best at analysing that kind of thing and it seemed at first glance that the evidence shared was somewhat contradictory. So I was concerned that I would end up inadvertently talking rubbish in this post.

And then I realised that this is exactly the problem. I am a woman of childbearing age who has had an education to degree level, English is my first language and I discuss birth and maternity pretty much every day. When we talk about informed choice we mean sharing all of the evidence plus the benefit of experience with pregnant women and their families, so that they can go through it and make their own decisions. Yet if I were writing this today as a woman who had been told she was likely to have a “big” baby I would be confused. And a little scared.

So it’s a good job I didn’t know any of this when I confidently went on to give birth to my 8lbs 13oz son on all fours on our bathroom floor.

Let’s pretend for a moment that I am in my third trimester and have been told by my midwife that she suspects baby is going to be a big ‘un. Probably a bouncing 9lbs tot. Before I go down the route of “doing” anything about that, or amending my birth plans, I have asked the #MatExp group for some information. What have I discovered?

Well, firstly we need to know a little bit more about this fictitious me. Do I have gestational diabetes? Am I classed as overweight? No? Okay then, we can stick with our issue being only the predicted size of my baby and keep questions of GD and BMI for another day if we may. Similarly, we will assume that I am physically able. So why are people sucking their teeth and looking concerned that baby might be of a generous size?

This is where we come to shoulder dystocia. “Shoulder dystocia is when the baby’s head has been born but one of the shoulders becomes stuck behind the mother’s pubic bone, delaying the birth of the baby’s body. If this happens, extra help is usually needed to release the baby’s shoulder. In the majority of cases, the baby will be born promptly and safely.” (From https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/patients/patient-leaflets/shoulder-dystocia/)

In the majority of cases, the baby will be born promptly and safely? So what’s all the fuss about then? Well let’s look at this passage from the abstract of this article:

“Shoulder dystocia remains an unpredictable obstetric emergency, striking fear in the hearts of obstetricians both novice and experienced. While outcomes that lead to permanent injury are rare, almost all obstetricians with enough years of practice have participated in a birth with a severe shoulder dystocia and are at least aware of cases that have resulted in significant neurologic injury or even neonatal death. This is despite many years of research trying to understand the risk factors associated with it, all in an attempt primarily to characterize when the risk is high enough to avoid vaginal delivery altogether and prevent a shoulder dystocia, whose attendant morbidities are estimated to be at a rate as high as 16–48%. The study of shoulder dystocia remains challenging due to its generally retrospective nature, as well as dependence on proper identification and documentation. As a result, the prediction of shoulder dystocia remains elusive, and the cost of trying to prevent one by performing a cesarean delivery remains high. While ultimately it is the injury that is the key concern, rather than the shoulder dystocia itself, it is in the presence of an identified shoulder dystocia that occurrence of injury is most common.

The majority of shoulder dystocia cases occur without major risk factors. Moreover, even the best antenatal predictors have a low positive predictive value. Shoulder dystocia therefore cannot be reliably predicted, and the only preventative measure is cesarean delivery.”

Ah, okay. So whilst MOST cases are not a problem, when there is a problem it can be very serious. And most experienced obstetricians will have seen this happen, inevitably influencing their perception of the risks involved. The teeth sucking is a bit more understandable now.

Apparently if I have a small pelvis it is more likely that baby will get his shoulders stuck. How do you know if you have a small pelvis? Small compared to what or whom? I have no idea but it appears to be a consideration. One birth professional observed that “to me that ‘big’ is subjective in a lot of cases. A 7lb baby could be big to one woman whereas a 10lb baby could be average to another. There needs to be far more than just the picture provided by a (often inaccurate) scan. Woman’s own birthweight for example, her stature etc.” It was mentioned that pelvimetry used to be widely used but has been abandoned in favour of scans, due to a Cochrane review that found these measurements did more harm than good.

There is a higher likelihood of shoulder dystocia in bigger babies, that much is undisputed. Yet the language used when discussing this risk makes a big difference to how a pregnant woman might view the risk. Contrasted with the passage above is this from Evidence-Based Birth:

I suspect as with so many birth choices, women are likely to get the reassuring language from midwives who have confidently dealt with many instances of stuck shoulders, and more wary language from obstetricians who have seen first hand what can go tragically wrong.

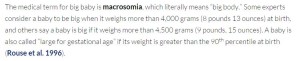

So in summary shoulder dystocia is more likely in bigger babies but on the whole it can’t be predicted and can usually be dealt with. It turns out that there are arbitrary cut offs for recommending Caesarean to prevent SD – 5kg in a non-diabetic woman. That means nothing to me but a quick Google tells me that is an 11lbs baby. My hypothetical nine pounder doesn’t warrant an automatic recommendation for a c-section then. So far so good.

But what position is my baby in? This is an important factor. I would argue that all pregnant women should be aware of foetal positioning and how to optimise it, but in this case it is particularly important as a malpositioned big baby could cause trouble. Let’s assume though that I have been on spinningbabies.com, haven’t been reclining on the sofa, have been doing headstands for nine months or whatever it is that is recommended. Baby is now head down and engaged and we’re ready for the off.

At this point it’s good to know that there is no evidence to suggest that it hurts more to give birth to a big baby. I cannot comment as my firstborn is the only child I have birthed vaginally so have nothing to compare it to. But the midwives on the group have been reassuring that being predicted a “big” baby does not mean increased pain in labour. Good stuff.

What I haven’t done (but what might have been recommended to me) – I have not had a growth scan. It appears that growth scans should be used to identify small babies (a discussion for another day no doubt) but not big ones. One group member commented “Ultrasound scans become increasingly unreliable the further along in pregnancy they are performed. Weight is an ESTIMATION can be up to 25% out either way. They base it on the abdominal circumference, head circumference & femur length – try doing it with yourself & see how accurate it is!”

A birth professional went on to say “Growth scans are pretty hopeless in the third trimester – the only thing that is useful is a regular plotting of growth to try to identify a sudden growth spurt that could indicate a problem. A one off growth scan late on in pregnancy basically just leads to unhelpful fears on all sides.”

Which begs the question, how do we identify the potential 11lbs babies who “require” a c-section birth?

So I haven’t allowed anyone to worry me further with a most likely inaccurate scan reading. We think baby is going to be big but not so big that I am going to be encouraged to have an elective c-section, so I’m happy to go ahead with my vaginal birth.

This is where we come to the issue that dominated the discussion. The position that women labour in can make a HUGE difference to the outcome when they are birthing a large baby. Labouring on their back is most likely to be unhelpful. Labouring on all fours is most likely to enable them to birth without intervention. Certainly my experience – I could not bear to be in any position other than kneeling up for my entire labour, simply could not bear it. Lying down was absolutely out of the question.

One group member had a wealth of information to contribute and commented “There’s plenty of evidence to support programs like birth ball use, not just gentle bouncing but using as a structured exercise plus also designing maternity units/rooms to encourage movement and position changes and upright movement.”

A midwife explained “I worked with a lovely obstetrician a few years ago (I have worked with many wonderful obstetricians). She was leading the skills and drills component for obstetric emergencies of the yearly mandatory training. We were practicing what to do in the case of a shoulder dystocia with a mannequin. She looked at me and said, of course we all know that if we do this (turning the model over in to what would be an all fours position) we wouldn’t have to be doing this at all.”

And one of our obstetricians added “in terms of labour progression, size is not nearly so important as baby’s positioning and flexion.”

The impact of pain relief was also mentioned: “Of course this is impacted by maternal position too, often compounded by an epidural that softens the pelvic floor muscles reducing the baby’s ability to rotate on the pelvic floor.”

Let’s recap. My midwife has said that it is her experienced opinion that I am going to have a big baby. I have declined a growth scan but we are both confident that baby won’t be topping 11lbs. So we’re going for a vaginal birth, and have done everything we can to ensure baby is in a good position. I am then being encouraged to be active in labour, labour on all fours and so on. There is no reason to believe that I will experience more pain due to baby’s size. There is an elevated risk of shoulder dystocia but my birth team are trained to deal with that. Hmm, okay, on reflection I would make the same choice I made back in 2011 when I hadn’t had this conversation. Home waterbirth with experienced midwives please! Especially, for me as an individual, “big” babies are normal – I was 9lbs 11oz at birth myself.

Does the above sound like the experience most women have when a big baby is predicted? Let’s ask some real life women shall we? Here I am indebted to the fabulous women on my other Facebook group who have shared their stories with me.

“I was told I would have a big baby. The midwife measured me way off the chart at 36 or 38 weeks can’t remember which. Went for growth scan. Again measured me pretty big. Appointment with consultant, he measured me big. Straight aways did a growth scan. I was then booked in for an induction the following week. Was in from the 25th and had him on 29th (due on 5th July) he was only 8lb 2oz.” What was the reason for the induction? “Not sure. They said as it was my first I probably would go over so as he was measuring big now it could be more of an issue in 3 or 4 weeks.”

“My 1st baby was 9lb 14oz and got stuck with shoulder dystocia and born with the ventouse.” And what positions were you labouring in with baby no. 1? Were you on all fours at all? “No! I believe position/ventouse were what caused her to be stuck! I was dehydrated so they made me stay in the bed on my back to be monitored!”

“I was told my little boy was a big baby and I had to have a growth scan. I was then induced a week early due to his size. He weighed 8lb 15oz and I had a 4th degree tear and had to be rushed to theatre.” What did they say were the risks with him being big? Did they explain why they wanted to induce you? “The explanation for me being induced was if I was left and went over I would have had a tough time, but looking back now I wish I had opted out of being induced as I blame that for the complications.”

“I was measuring big for dates at my midwife appointments from about 24 weeks. I was eventually sent for a scan to rule out polyhydraminos at about 32 weeks. The scan results were ok and showed that my baby’s measurements were on the 95th centile. I was then changed to higher risk consultant led care. They told me it was due to the baby’s size and the increased need for intervention during delivery, e.g. forceps, etc. My baby was predicted to be 9lb 9oz maximum and she was actually 10lb 6oz. I was in slow labour for 6 days. I had to have an oxytocin drip to get me from 7cm but I couldn’t get passed 8cm as her big shoulders meant her head wouldn’t press down on my cervix! As a result of being on the drip, I wasn’t able to get in different positions in labour and was mainly confined to the bed. I then had an emergency c-section due to failure to progress.” How did all the talk of having a “big” baby affect how confident you felt in being able to give birth? “To be honest, it did affect how confident I felt giving birth. I was then very nervous at the prospect of tearing or that I’d have difficulties during the birth and would need forceps, etc. I was very worried that something would go wrong. To be honest, I felt very relieved when the consultant said I needed a c-section.”

I commented that I wondered whether that was the reason the mum above struggled to dilate. Rather than failure to progress perhaps her caregivers should be have been labelled with “failure to encourage”.

There was one rather different story, although the mum in question was surprised by how her consultant’s advice varied from what others were experiencing: “Was told based on my daughter being 10lb that my little boy would be big. The midwife referred me to a consultant as my fundal height was bigger than even my little girl was! Tested me for GD which I didn’t have. Consultant said he was going to do absolutely nothing about it which varied massively from my peers at nearby hospitals who were being induced early. He said inducing a large baby is dangerous as they’re more likely to get stuck and if I got my little girl out this one would be fine! Bit worried but I trusted him.”

And what of those women who had not been told to expect a big baby?

“I had a 9lb 4oz baby but wasn’t expecting him to be ‘big’ I had a tiny bump and was told he was only going to be about 7lb. I had him naturally with no complications at all. A few stitches externally but that was all.”

“My 2nd baby was 9lbs 6oz and no one knew he would be that big as my first was 7lb 11oz. Labour was very quick and vaginally delivered with 1 stitch.”

“If 9lb2oz is classed as a big baby then mine was! He was 13 days over so probably wouldn’t have been so big if I’d gone on time. Nobody told me he was going to be big at any of the extra monitoring appts I had the week before he arrived all on his own, no help, drugs or hospital. I did tear slightly but midwife was happy for me not to go to hospital if I didn’t want to.”

“I wasn’t told I was going to have a big baby, I was tested for diabetes at one point because my bump had grown quite quickly but I didn’t have it. My little boy weighed 9lb 15oz, I was in labour for 6 and a half hours and didn’t have any complications. I had a few stitches afterwards but nothing major.”

What can we say in conclusion? When a baby is identified as potentially being “big” are all families given the information that we have discussed here? Do all birth professionals agree with the general thrust of this post or have some important points been missed or misrepresented? And if I have got it all wrong what does that say for the idea of “informed choice”? Because this is my best understanding of the issues following a detailed discussion with experienced birth professionals. There are plenty of other birth stories from the mums on my group which make it clear that women are routinely being encouraged down the route of induction without fully understanding why, only that baby is going to be “big” and that is some kind of a problem. And so many of these stories end in instrumental deliveries, emergency c-sections and, at worst, traumatic births. Would it not be preferable for women to have the issues fully explained to them and to be encouraged to have an active birth where, in all likelihood, they will be capable of giving birth to their child?

I am just glad that my “big” baby is here, safe and well, and now in his second week at primary school. Decisions always seem simple in hindsight.

Some of the links that were shared as part of the discussion not already linked to above:

Shoulder Dystocia – RCOG green top guidelines

Rebozo Technique for Foetal Malposition in Labour

The Effect of Birth Ball Exercises during Pregnancy on Mode of Delivery

After Shoulder Dystocia: Managing the Subsequent Pregnancy and Delivery