This post has been written for the #MatExp campaign by Claire Flower, Clinical Specialist Music Therapist and Joint Team Lead for the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. Our thanks to Claire and her team for their support for #MatExp.

***********************************************************************

‘Music While You Wait’ is the working title of a project we’re recently been running in maternity care at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London.

My name is Claire Flower, and I jointly lead the music therapy service here at Chelsea and Westminster hospital. We have had a large children’s music therapy service for many years in the Trust, but recently we’ve had specific funding to explore how music is used by, and can be helpful for, women through pregnancy and birth. The project title – ‘Music While you Wait’ – has seemed fitting, both because of pregnancy itself being a waiting game, but also because the project has been based in the antenatal waiting areas of the hospital.

In conversations with midwives, doctors, pregnant women and partners one of the themes which kept popping up was that the experience of attending, or working in, an antenatal clinic can sometimes be extremely stressful. People told me that at busy times the clinics are often full and noisy, some women may have children with them which brings its own pressures, some may have lengthy waits to be seen, and some may be anxious about being there for all kinds of reasons. As one woman said to me, ‘not everyone here is happy’.

There was a real, shared interest in exploring together how music might be one way of making the experience of the clinic better for everyone, lowering stress levels, reducing anxiety, and giving different opportunities for social contact and connection.

We agreed that I would attend 6 different clinics, offering live music, as well as talking with women, partners and staff about music in pregnancy and beyond. And so we started – wheeling an electric piano into the waiting area, playing a range of music, talking, and being prepared to see what unfolded.

Over the weeks, I kept a journal, describing events in each clinic, and thinking about them in preparing for the next one. Looking back at them now, they give a flavour of some of the moments which characterised the project.

For example, how the piano music was received by women coming to the clinic…..

‘One couple arrive, and as they walk in she looks across and says quite loudly across the room, ‘oh it’s you!’. There’s surprise from both of them that the music is live, they’d assumed it was the radio. ‘There’s just something about having the person, you know?’ she said.

On the same morning….

‘Another woman smiles frequently at me as I play and she waits. In fact, she moves from sitting with her back to the piano, to facing me and sitting closer. As I stop to respond to someone’s comment, she agrees that it’s lovely, and says she was just texting her sister to say how lovely it is to sit and listen to. Makes me think that music is doing its work of rippling outwards to unexpected places!’

In this busy clinic, women often come with children – quite a challenge if there’s a lengthy wait. When one woman arrives with two energetic young children, looking quite exhausted, I wonder how I might be able to help with some music for them….

‘I come away from the piano, and bring out some small instruments for us to use, crouching down with them to sing. Mum joins in, and the children begin to sing and dance, moving rhythmically to the music. Looking around, I see other women smiling at the children, or even moving a little to the music…. After a good play, we agree to put the instruments away (I’m really not sure how the sound levels will have been for the poor midwife in the room nearest to our impromptu band!), and somebody in the room suggests it’s ‘time for a lullaby’, I return to the piano, and we have a gentle rendition of Twinkle Twinkle, one of the children ‘twinkling’ at the top of the keyboard.’

And then there was the morning when this happened…..

‘As I’m playing, one woman, quite heavily pregnant, walks in, looks towards me smiling, and walks towards me. She approaches so confidently, and with such a smile that I wonder whether we know each other, or that I’ve forgotten meeting her here previously…..’

What unfolded from that point was one of the highlights of the project for me, but she’s best placed to tell you about it herself….

“I am a professional violinist. In July 2016 I was almost 9 months pregnant with my second child and was suffering from gestational diabetes. So every Tuesday until my C section I had to go to C&W and be assessed by a diabetes specialist nurse or consultant. I was very anxious and tired beyond belief. On top of that, more often than not there was a rather long wait for the appointment.

Needless to say I wasn’t looking forward to Tuesday…until one day when I walked in and heard music. There was soft classical music coming from a speaker or two (I thought for a few seconds until I spotted the real source, at the back of the room). SOMEONE (not something!) was playing that lovely music. How amazing, and how very rare…

I walked straight towards her with no doubt in mind of what I was going to do. I had to come here, bring my violin and play with her, even if it was just for a few minutes! I had been pregnant and breastfeeding for three years by then and playing the violin had LOST ITS place in my life. I did miss it desperately and said it. To my absolute joy Claire invited me to bring some music as well the following Tuesday, before my appointment and play with her for almost an hour. We discussed the music in detail (not everything suits so I took her advice and offered to also bring something a little different to see if and how it might work).

I counted the days until my next appointment, even managed to practice a little for the first time in years, searched for my beloved but long forgotten music and didn’t think of anything else other than how wonderful it will be to join Claire and play for everyone there who was going through the same hard times as I was. It was also the first time my daughter listened to me play the violin in public. I felt like the luckiest and most privileged woman on earth (no exaggeration here!).”

For everyone who was lucky enough to be working, or coming to the clinic on the day when this happened, it was a magical moment. It certainly ticked the box of seeing how music might make the antenatal clinic experience better for everyone there.

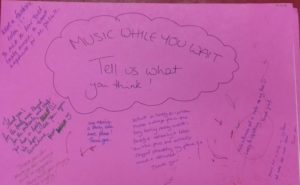

We’re writing the project up now, using, among other things, the comments which were written and drawn for us by women, children, staff, and partners in each session.

And we’re discussing what we do with it next, which might mean developing it further in the waiting areas, as well as thinking about how it might translate to the wards.

As Viki Girton, Lead Midwife for Antenatal Clinics says ‘Music While You Wait helped to create a relaxing environment for staff and patients… having more would be fabulous to improve maternity experiences and patient satisfaction here’.

I love being a music therapist, but being able to step into the maternity world and work with such a great group of women, staff and families has been a new pleasure. We’re really excited to have conversations with anyone interested in where we take this next, and how music therapy might play a part in #MatExp!

Claire Flower

February 2017